1. CUT THE HYPERBOLE

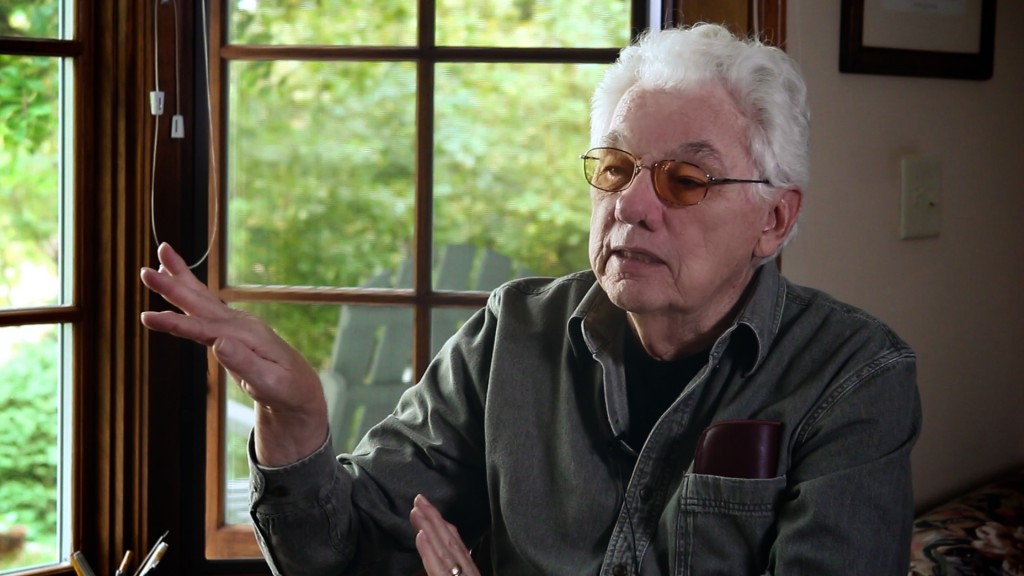

Before the interview began Gordon said

Our job isn’t to recreate reality, our job is to represent reality.

He was saying that no matter how you slice it, photography is art. There isn’t a hierarchy of realism over other styles, because in truth, “realism” doesn’t even exist. The question is how do you use the tools available to tell a story.

Being “realistic” isn’t the be all and end all; and this is from the guy who was noted for making photography in movies much closer to natural than it ever had been before. But he never pushed that agenda. He just wanted to make things look a certain way.

Sounds basic enough but he never used the word “naturalism”. Not once. Later on he stated

I just think about….what I want it to look like.

He also used “good” and “bad” a lot to describe things. He doesn’t use words strung together that don’t mean anything. He doesn’t talk about his work in ways that aren’t simple. And that’s the way he worked, with simplicity. Working to achieve simplicity, as I’d come to find from talking with him, might be much harder than you think.

While the most complicated idea might be being expressed, it was and is Willis’ approach to discuss choices and photography in the clearest possible way.

While there are different ways to work, a great approach is to cut the hyperbole. Be straight and direct in figuring out what you’re doing and how you’re going to do it. Sounds simple but it’s harder than it sounds.

Part of this equation is asking really basic questions while shooting, “what are we trying to show?” “Will this look good?” etc. Get back to your eight year old self and start thinking on a basic level again.

2. SHOOT TO CUT

Quickly into my conversation with him, I realized that Gordon was talking about how shooting relates to cutting. And at that point he basically said that cutting was everything. He doesn’t shoot to have a close-up, or a wide, or something well lit. He shot to tell the story.

This matters both in terms of how something is relayed to an audience – a scene, for example – and also how one transfers between scenes or places or moments. He related his feelings on B&W films from the 30’s and 40’s.

You’ll have two people talking, or fighting, and they’ll be in a two shot. (Boom, he gestures the shot, a straight on two shot). It plays really well. So why would you cut?

He was expressing what he did so well in so many films. He would think of the scene and if there was a simpler way to shoot it, and know that it would cut into the movie as a larger whole, he would do that and make that choice. Or at least he would try to make that choice if the director was open to the idea.

When you watch Gordon Willis’ films you note that everything cuts together fairly seamlessly. Even in sequences where a lot of the shots are really dark or might be confusing when separated from the whole, once combined with the other shots they’re perfect.

He always says, “you have to have the whole movie in your head, from beginning to end, at the same time.” Now to be clear this doesn’t mean that he’s determined how the movie WILL be cut. He hasn’t. What he’s determined is a lot of information about how it might be cut. He incorporates those options into what gets shot to help narrow down the possibilities and keep the story focused.

He was also a master of knowing what transition shots would work from one scene to the next, which is also very difficult. YES, his lighting was amazing, but he was focused first on what was going to be in a shot to reveal the information of the story step to step. The look came next. And probably way, way, way down the line is “what would be a cool shot?” I highly doubt that this was his focus, if ever. If a cool shot happened, it happened in the context of what he was doing–shooting to cut.

Did he have the “look” of the film in his head? Sure. But before that came the idea of what shot was before and what shot was after. In other words, what cuts.

Note: this is not a suggestion to directors or photographers to shoot in such a way that an editor cannot elyptically shorten, lengthen, or change a scene. God forbid. Not many people have the exact instinct that Gordon has, obviously. But his point can be internalized and applied much more often than you might think. Sometimes you can do a scene in a “1’er” if you know for sure it’s going to work in the final film.

3. BLOCKING IS CUTTING

On stage, blocking is the movement and positioning of the actors between one another. In film, blocking is all that plus where the camera is, what it does and what lens is used. This means blocking for film is at least three times as complicated. Ultimately, this was the most important aspect of how to execute the shooting of a scene for Gordon. Certainly, it was more important than the lighting. And in many cases, probably makes the lighting much easier to achieve.

By focusing on how the story needs to be told (i.e. what you see and when you see it,) it allows the photographer and director to choreograph first and then think about how these choreographed moments will cut together.

Here’s a short clip of Gordon the relationship of directing and cutting

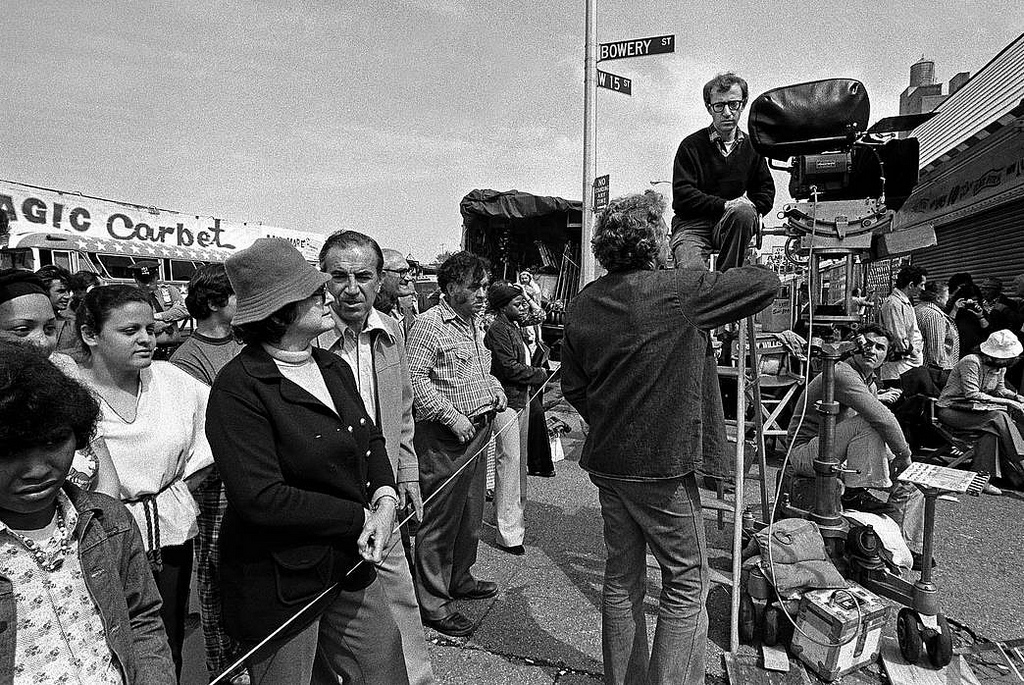

It sounds obvious but it is most often tossed out with the trash when people get onto the set. Then comes the “need the close up, need the long shot, get this get that”. The basic rules are forgotten. Many of Woody Allen’s greatest moments came from not just how they were written or performed but how they were played in front of the camera. This allowed for speed, economy and simplicity in the storytelling. Countless examples from Annie Hall, Manhattan, Stardust Memories etc. Mr. Willis was instrumental in this.

By focusing on the blocking and how the actors might move in and out of frame, or how the camera might wait to follow them, led to figuring out what played well and then how to connect the dots from one scene to the next.

Basic thinking with very, very articulate and refined results.

To be clear, blocking is the physical position of the actors, and the camera, and the motion they all make within a shot from beginning to end. If one places a strong effort and focus on blocking, before worrying about lighting or look, it may very well make the entire filming process go much, much smoother. But, more importantly, it will also be the first definition of how your film actually looks and feels. Changing the blocking can change everything, how the story is told, and what the story actually is.

4. LIGHTING SHOULDN’T BE DRIVEN BY INSECURITY

I’d like to make this a “should” but at the end of the day, it’s easier to summarize what Gordon felt on this subject via a negative. Because this is what happens 90% of the time. Photographers too often light to make things look “wow” instead of first blocking the shot, using the camera and the space and the actors, and then (and only then) involving lights and making things glisten.

While lighting is never “easy” it can be made very simple if you are operating from a point of security in what you’re doing. Most people aren’t, they’re operating from insecurity. The same gene that wants to over-complicate a story is the same gene that wants to over shoot and over light. And quite simply that’s bullshit and doesn’t help anything.

Everyone remembers the Brando lighting in Godfather which he simply states was motivated partially by Brando’s makeup and partially because he wanted to open the movie in this cave-like setting, juxtaposed against the wedding outside.

Think about the planetarium sequence in Manhattan. . It’s extremely dark and the actors are entirely in silhouette. Think about the walk and talks in Stardust Memories. No lights. Hardly ever with wide day exteriors for him. They look beautiful because they’re right for what the story is at the time.

YES, Gordon was aware of what the film “should look like” but that was more based on an overall instinct and consistency of feeling with which he approached a given project. Lighting the scene fit into that bigger picture after he had blocked the shot and figured, “what was the simplest and most beautiful way to light this shot now that I have it already positioned?” If that meant you don’t add the foil for this actress and the highlight for so-and-so, so be it.

Mr. Willis wasn’t worried because he was getting the pieces of the film together first and foremost. He was very secure in his choices and free to explore simplicity if that mean lots of lights, few lights, one light, or no lights. That’s the point.

5. HAVE A REASON FOR YOUR CHOICES

The one thing that ties together everything is that every choice was based on a solid reason. Gordon often used a 40mm lens. Why? Because it felt right to him and because he felt the perspective of the lens best allowed him–yes him, and by extension the audience–to see what was happening in a reasonable way.

He also said that he sees the world from roughly his own height. Sure there were other times when he used other lenses or other heights to shoot from but it was because the scene, the blocking, the cutting, demanded it.

In order to simplify his work space he stuck with tools that were comfortable and intuitive and then worked from there. He needed a reason to go high-angle, low-angle, wide, long, etc. Most of the time choices are made by a desire to ramp up style as opposed to really looking at the sequence, figuring out how best to tell it and then executing with simplicity.

So while it’s okay to do something fancy, there has to be a reason for it. In the overhead shot of Library of Congress in All the President’s Men Gordon’s first reaction to the scene was, “how do we show the idea of a needle in a haystack?” So out came the winch and the rig and everything else along with it. And the shot is stunning. But you don’t do that unless it’s necessary and you’ve been naturally bumped away from basic principles.

If you have an honest realistic reason as to why you want your film to look a certain way; a reason why a scene should be cut up a certain way; why it should be staged and lit the way you want it; and, why it needs to be whatever color palette you’re playing with, you stand a better chance of getting out of the story’s way instead of smothering it in style that doesn’t help anyone.

Want more Gordon Willis, you’ll enjoy these:

Watch part 1 of the interview

Watch part 2 of the interview

Listen to the uncut podcast

Other posts you may enjoy:

5 Cinematographers You Should Follow on Twitter

5 Things to Learn About Editing from Dan Lebental (Thor)